Centralization is inevitable

...but decentralization is right behind it

I would like to decentralize the web somewhat. Unfortunately, designing an idealized architecture won’t be enough to do it.

Consolidation tends to sneak into systems, often in surprising places, and frequently through some aspect we might feel is “outside” of the system.

So, if you happen to want to decentralize, it helps to know how and why centralization happens in the first place.

Centralization as a spectrum

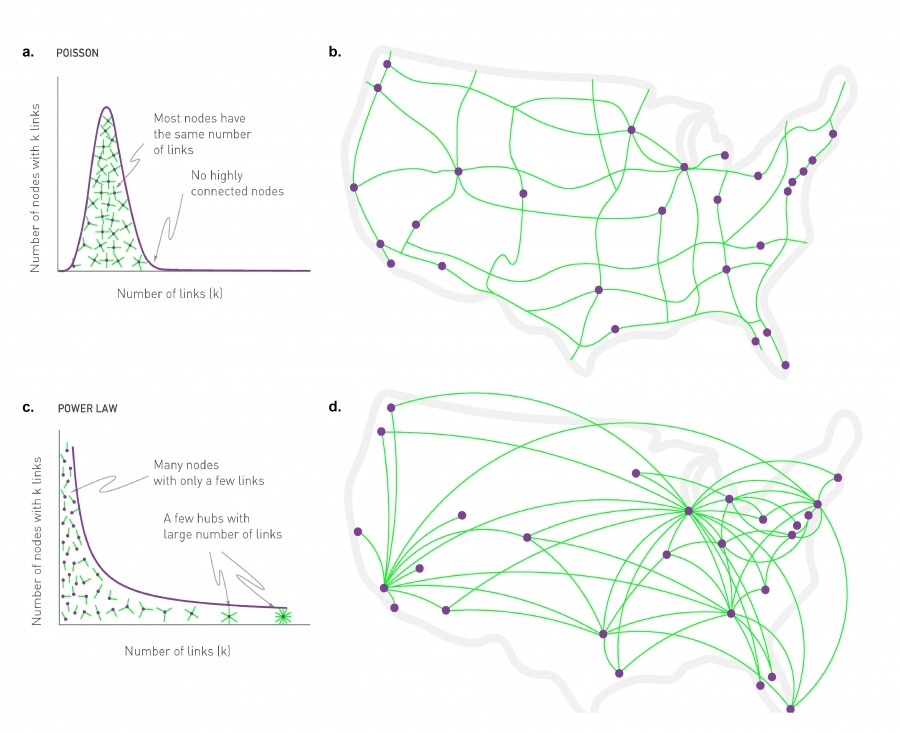

Ok, first, what do we mean centralization? One sense of centralization is total centralization, a network with a single hub (leftmost figure). But it’s also common to talk about highly consolidated networks as “centralized”. Think banking systems, social networks, or the smartphone duopoly. These consolidated systems happen to have more than one hub, but not that much more. I want to think about about centralization in this sense. Highly consolidated.

What about decentralized networks? We might picture an idealized flat network, fully distributed (rightmost figure). Every node is equal in power and function, evenly, or at least randomly, distributed. There’s just one problem…

Networks aren’t evenly distributed IRL

Here is a map of the internet. The first thing you might notice is that the internet is not evenly distributed. Instead, we see the emergence of densely connected hubs—centralized islands in the net.

This kind of thing is called a scale-free network. It seems that something like scale-free structure emerges repeatedly within evolving networks, including on the internet, the web, social networks, airline routes, co-authorship in scientific papers, power grids, inter-bank payment networks, Bitcoin mining, train routes, gene regulatory networks, protein interactions, ecological food webs, oligarchies, neural networks…

In fact, it turns out that almost all real-world networks have degree distributions with a tail of high-degree hubs like this. (Newman, 2018. Networks.)

If you see a pattern emerge over and over, it’s a solid bet there are evolutionary attractors pulling the system in that direction. And yeah, it turns out scale-free networks have strange and important structural properties.

Scale-free networks are power-law distributed

The defining characteristic of scale-free networks is a power law distribution with a long tail. A small number of nodes with an extremely large number of links, and an extremely large number of nodes with a small number of links. Think Twitter. Most users have a few followers, while a few influencers have millions.

This power law distribution grants the biggest hubs a lot of power over the network. It also makes hubs important to the functioning of the network in ways that are not immediately obvious, like keystone species in an ecology. But what makes a network evolve this power law distribution?

Scale-free networks emerge due to preferential attachment

Preferential attachment is any rich-get-richer feedback loop. We run into preferential attachment all the time in software, in the form of network effect:

The value of a telecommunications network is proportional to the square of the number of connected users of the system (n^2). (Metcalfe's Law)

And it’s not just telephone networks. Any snowball will do…

Network effect. More users mean more users. Think Facebook or Twitter.

Attention: More attention means more pricing power means more content means more attention. The Netflix model.

Trust: More customers means more social proof means more customers. Dunbar’s Number suggests we can’t keep track of more than 150 people and when it comes to trust, brands are people too. I don’t want to saturate my 150 friend limit keeping track of brands, and so that means hubs. This is one reason why there are just a few big banks, for example.

Early-mover advantage. Crypto and VC both have this property. Early adopters make much more than late ones. Interestingly, this curve is inverse of the network effect growth curve, so tokens can be used as incentive to bootstrap new networks.

Economies of scale. More scale means more scale. If you are AWS or Azure, more scale means cheaper unit economics means lower prices means more customers means more scale.

Capital: more money makes more money. Classic.

…That hits a lot of the big ones. In general, look for any rich-get-richer compounding feedback loop.

Scale-free networks emerge because they are efficient

This is something that p2p projects have repeatedly rediscovered. Flat networks perform poorly. Hubs are efficient.

Peer-to-Peer (P2P) networks have grown to such a massive scale that performing an efficient search in the network is non-trivial. Systems such as Gnutella were initially plagued with scalability problems as the number of users grew into the tens of thousands. As the number of users has now climbed into the millions, system designers have resorted to the use of supernodes to address scalability issues and to perform more efficient searches.

(Hadaller, Regan, Russell, 2012. The Necessity of Supernodes)

Hubs act as routers through which information can travel from A to B to C, efficiently.

Distances in a scale-free network are smaller than the distances in a random network. This is why airlines build hubs, for example. In fact, while in a random network the average number of hops to get from anywhere to anywhere is log(n), in a scale-free network the number of hops only grows as a function of log(log(n)). Hardly at all.

This makes even the most massive scale-free networks ultra-small worlds. You can traverse the network in just a few hops.

Scale-free networks emerge because of selection pressure

In an ideal distributed internet, we might all run personal servers from a closet. But we do not live in an ideal world, and running a reliable server is difficult. Computers crash, hard drives die, traffic will spike and your server get swamped. This is why people don’t want to run their own servers, and never will.

So, servers go down sometimes, and some go down more than others, and this is another reason scale-free networks emerge. Reliability, scalability are selection pressures. Fitter nodes attract more connections just by virtue of staying alive. Eventually this results in hubs. This is the Fitness Model of scale-free networks.

Scale-free networks emerge because they are resilient to failure (yet vulnerable to attack)

Ecologists believe that the hubs of food webs are the keystone species of an ecosystem, paramount in maintaining the ecosystem's stability.

(Barabasi, 2002. “Linked”)

If you choose a random node in a scale-free network and knock it out, the network won’t even notice because almost all nodes have just a few connections. You’re unlikely to hit a hub. Random bad luck is a constant, and scale-free networks are robust to bad luck.

Yet this same structural property makes scale-free networks very vulnerable to targeted attack. Even so, just knocking out one hub is usually not enough. But knock out a few, and the network collapses (Barabasi 2016. Network Science, ch 8).

Good thing Nature isn’t in the business of targeted attacks! But humans sometimes are. Also sometimes hubs do get wiped out by chance. Asteroids happen! Either way, this destabilizes the entire network. Which brings us to…

Networks evolve from distributed to centralized and back again

Networks also have a time dimension, and the shape of the network changes as it ages. Ecosystems exist in punctuated equilibrium, repeatedly evolving through distinct phases of randomness, growth, consolidation, and collapse.

(Phase 1) Random: The system is unstructured. Random events occur without particularly changing the structure.

(Phase 2) Growth: An innovation causes a major phase transition within the structure of the system. The innovation catalyzes other innovations in a positive feedback loop.

(Phase 3) Consolidation: Growth rates saturate. The ecosystem consolidates into a highly organized network, optimized for efficiency, as each agent seeks to eke out as much as it can from its position in the value chain. Hubs (keystone species) appear at critical points.

(Phase 4) Collapse: A random shock, or new innovation demolishes one of the keystone species, causing cascade failure within the highly structured network. The ecosystem collapses into a random structure.

(Repeat): The system begins a slow crawl back up the evolutionary ladder of complexity.

(Jain, Krishna, 2002. Large extinctions in an evolutionary model)

It’s a good bet that you’ll experience this cycle of rebirth in any evolving network. We see it in everything from industries to ecosystems.

He not busy being born is busy dying

The key insight is that this process has a direction, from decentralized to centralized, and collapsing back again.

And you may ask yourself, why not simply start with a centralized system? But now you’ve built an aging and dying system.

And you may ask yourself why not use some mechanism to force decentralization? But given the evolutionary pressures pushing a system in this direction, another network may just outcompete you.

It seems unlikely that the cycle of network samsara can be broken or reversed.

But perhaps we can lean into this cycle of rebirth and build new decentralized things, throw new parties. Perhaps we can build many decentralized things, and construct a rich ecology of interacting systems at different stages of growth, where any one extinction does not take everything down with it.