LLMs and hyper-orality

Large language models are transforming text into a new kind of spoken word

So after exploring LLMs and information post-scarcity, I had meant to write about Tools for Thought in the age of LLMs. But as I started to capture thoughts on this topic, a particular thread emerged that wouldn’t let me alone. It ended up growing into a whole post. Here goes…

The text speaks back

So, a friend recently shared an interesting experiment: wanderer.glazkov.com. By fine-tuning an LLM on his writing, he taught his blog to speak back.

When you first visit wanderer.glazkov.com, it will pull a few random chunks of content from the whole corpus of my writings, and ask the LLM to list some interesting key concepts from these chunks. Here, I am asking the narrator not to summarize or answer a specific question, but rather discern and list out the concepts that were mentioned in the context.

Then, I turn this list of concepts into a list of links. Intuitively, if the narrator picked out a concept from my writings, there must be some more text in my writings that elaborates on this concept. So if you click this link, you are asking the wanderer to collect all related chunks of text and then have the narrator describe the concept.

There is something very interesting going on here, and he’s not the only one pulling on the thread.

The common thread through all of these is text becoming conversation, transforming from static object to dynamic action.

It seems that if you compost an internet’s worth of written knowledge, the text starts to speak back. When pushed to its extreme, literature gives birth to a renewed orality. A hyper-orality.

Orality and literacy and hyper-orality

We’ve had about six-thousand years of literacy. Before that, it was hundreds of thousands of years of gathering around campfires, telling stories, sharing knowledge, imparting beliefs, from generation to generation to generation. We are an oral species, and only recently literate.

Knowledge in an oral tradition is a living thing that must be actively cultured. There is nowhere outside the mind to store it, so it either gets repeated, or dies.

To solve effectively the problem of retaining and retrieving carefully articulated thought, you have to do your thinking in mnemonic patterns, shaped for ready oral recurrence. Your thoughts must come into being in heavily rhythmic, balanced patterns, in repetitions or antithesis, in alliterations or assonances, in epithetic and other formulary expressions... Serious thought is intertwined with memory systems. (Walter J. Ong, 1982, Orality and Literacy)

In the living medium of the spoken word and communal memory, thoughts take on smooth curves, honed by the evolutionary selection pressures of telling and retelling over many generations. Theorist Walter J. Ong sketches out a number of emergent patterns that arise in this medium:

Aggregative rather than analytic: Communication is constructed from memetic phrases honed by generations of evolution: “the sturdy oak tree”, “the beautiful princess”, “clever Odysseus”.

Redundant: scenes, ideas, phrases are repeated, re-anchoring the story, giving it waypoints.

Situational rather than abstract: ideas anchored in things.

Close to the human lifeworld: Practical knowledge that solves common problems of life is repeated and shared.

Homeostatic: It takes a lot of active energy to maintain communal knowledge. Old memories that are no longer useful are soon forgotten. At the same time, continuity matters. There’s a deep respect for tradition, because if you lose it, and later try to get it back, it’s too late. This push and pull results in a homeostatic knowledge ecology.

Empathetic and participatory: Learning happens in "close, empathetic, communal association" with others who know. Truth emerges from communal consensus.

You can feel aspects of this when reading literature inherited from oral traditions. Emily Wilson gives us an example in the introduction to her translation of The Odyssey:

Dawn appears some twenty times in The Odyssey, and the poem repeats the same line, word for word, each time: emos d’erigeneia phane rhododaktulos eos: “But when early-born rosy-fingered Dawn appeared…” […]

In an oral or semiliterate culture, repeated epithets give a listener an anchor in a quick-moving story... In a highly literate society such as our own, repetitions are likely to feel like moments to skip. I have used the opportunity offered by the repetitions to explore the multiple different connotations of each epithet.

and so,

The early Dawn was born; her fingers bloomed.

When newborn Dawn appeared with rosy fingers…

When vernal Dawn first touched the sky with flowers…

But when the rosy hands of Dawn appeared…

When rosy-fingered Dawn came bright and early…

We rework words when putting them to paper, because text shapes our thoughts too. Different media culture different memes. Each medium constructs and supports different forms of cognition.

All media work us over completely. They are so pervasive in their personal, political, economic, aesthetic, psychological, moral, ethical, and social consequences that they leave no part of us untouched, unaffected, unaltered. The medium is the message.

(Marshall McLuhan, 1967. The Medium is the Massage)

LLMs work us over completely

LLMs are a new medium. How might this new medium rework our thinking?

Way back in the 70s, Walter J. Ong and Marshall McLuhan were predicting that electronic networks would reboot oral culture, and we can see this happening through social media. Memetic snowclone phrasing, communal sensemaking… It seems likely that LLMs will massively amplify and accelerate this ongoing effect, just as they amplify and accelerate the ongoing flood of information from the internet.

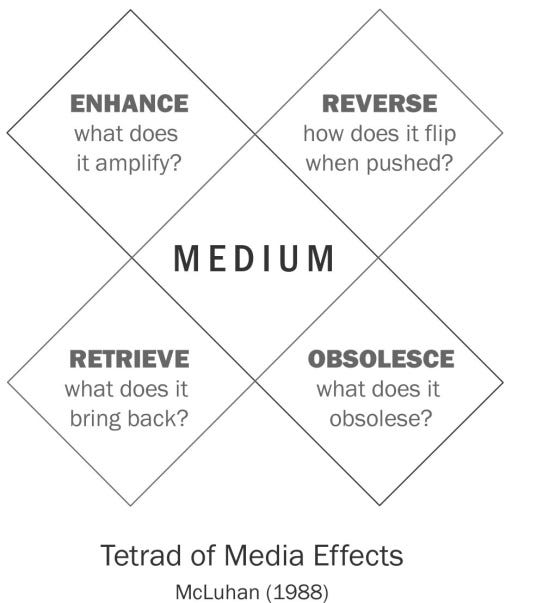

What else? So McLuhan has this interesting thinking framework called the Media Tetrad. It asks four questions: what does the new medium enhance, what does it make obsolete, what does it retrieve from our past, and finally, how might it reverse and the effects flip when pushed to extremes?

What if we look at LLMs through the lens of McLuhan’s Tetrad? Here’s my best attempt so far…

LLMs retrieve orality

LLMs enhance narrativization

LLMs obsolesce the author

LLMs reverse and become immersive hallucination when pushed to extremes

LLMs retrieve orality. This part we’ve covered. LLMs transform written language into conversation. You can chat with Plato, or Jung, or Dostoyevsky, or at least something that approximates the surface detail revealed in their writing.

LLMs enhance narrativization. LLMs are narrators, not fact-finders, or logicians. To ask them to solve math problems or do abstract reasoning is to look at them through the wrong end of the telescope. They’re inductive pattern-guessers, not deductive problem solvers. LLMs tell us stories, and will enhance our ability to tell stories.

LLMs obsolesce the author. The starring role of the author is a byproduct of the cycle time and one-way one-to-many relationship of print. Hyper-orality means everyone can tell stories, and we will tell stories communally. By conjuring up coherent narrative from stray scraps, LLMs will help us each express ourselves profusely, exploring and projecting our own subjective interior landscapes onto the world around us.

LLMs reverse and become immersive hallucination when pushed to extremes. The tendency for LLMs to hallucinate seems like the medium telling us something important about itself. LLMs when pushed to extremes will flood the zone with competing stories, causing all narrative sensemaking to break down into fever dream. And it isn’t difficult to imagine how LLMs might produce generative immersive hallucination when hooked up to a simple feedback mechanism and variable reward. Wireheading lite?

All of this is likely to be a multiplier for art and creative thinking, but also for cult and conspiracy. It’s going to get weird.

Our technology forces us to live mythically.

(Marshall McLuhan, 1967. The Medium is the Massage)