Possibility space

By this art you may contemplate the variations of the 23 letters.

Burton, The Anatomy of Melancholy, part 2, sect. II, mem. IV (1621)

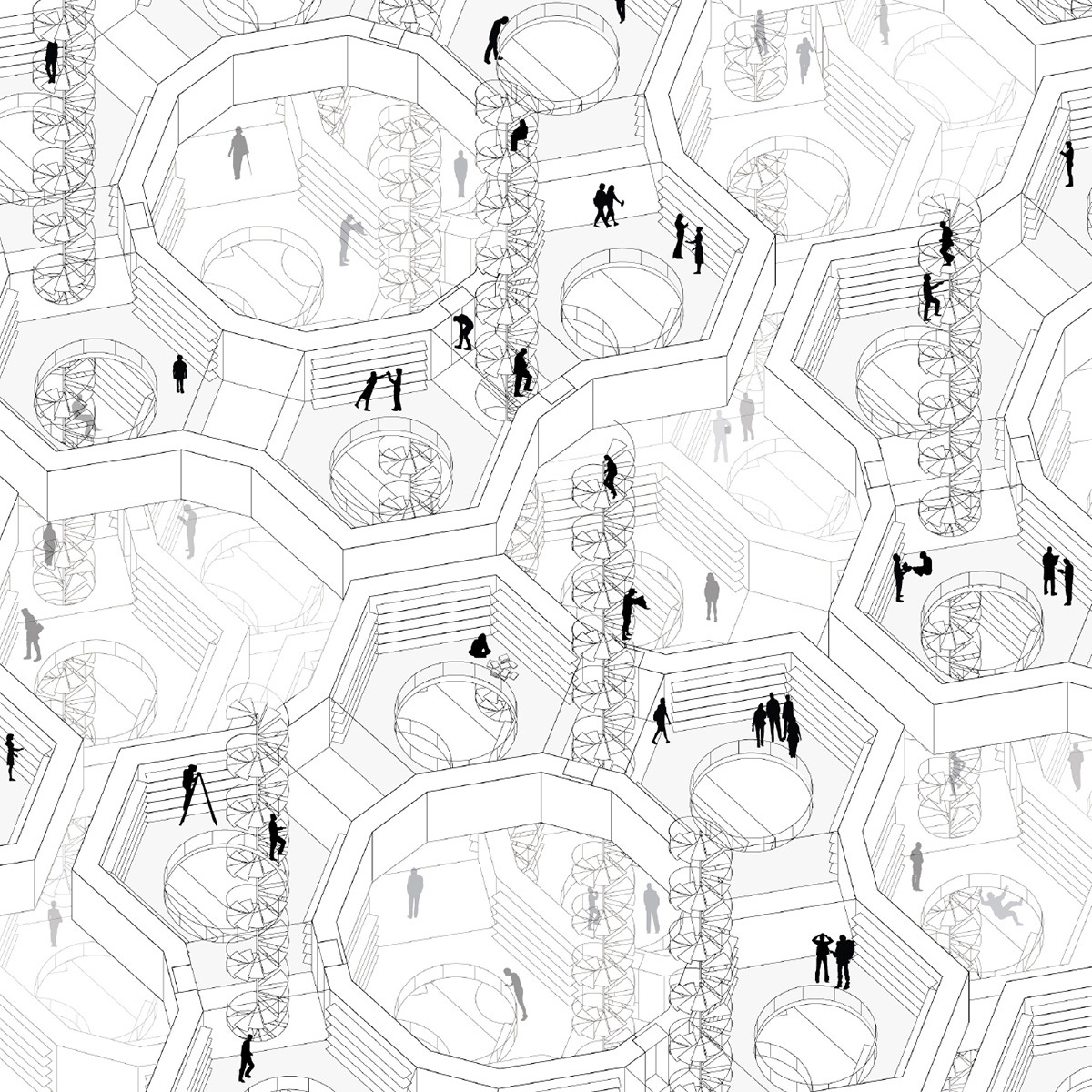

In The Library of Babel (1941), Jorge Luis Borges imagines a strange world:

The universe (which others call the Library) is composed of an indefinite and perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries, with vast air shafts between, surrounded by very low railings…

There are five shelves for each of the hexagon's walls; each shelf contains thirty-five books of uniform format; each book is of four hundred and ten pages; each page, of forty lines, each line, of some eighty letters which are black in color. There are also letters on the spine of each book; these letters do not indicate or prefigure what the pages will say…

Five hundred years ago, the chief of an upper hexagon came upon a book as confusing as the others, but which had nearly two pages of homogeneous lines. He showed his find to a wandering decoder who told him the lines were written in Portuguese; others said they were Yiddish. Within a century, the language was established: a Samoyedic Lithuanian dialect of Guarani, with classical Arabian inflections. The content was also deciphered: some notions of combinative analysis, illustrated with examples of variations with unlimited repetition. These examples made it possible for a librarian of genius to discover the fundamental law of the Library…

The Library is total […] its shelves register all the possible combinations of the twenty-odd orthographical symbols (a number which, though extremely vast, is not infinite): Everything: the minutely detailed history of the future, the archangels' autobiographies, the faithful catalogues of the Library, thousands and thousands of false catalogues, the demonstration of the fallacy of those catalogues, the demonstration of the fallacy of the true catalogue, the Gnostic gospel of Basilides, the commentary on that gospel, the commentary on the commentary on that gospel, the true story of your death, the translation of every book in all languages, the interpolations of every book in all books.

The complete set of permutations of all letters fitting within 410 pages.

Incidentally, a complete set of permutations is called a derangement—a permutation that leaves no element in its original position.

Related notes: Using a computer to generate permutations is a simple superpower for thinking.

There are other Libraries of Babel. In one corner of the multiverse, we find Borges’ Library, containing all possible combinations of letters. In another corner, there exists a concert hall containing all possible sounds. In still another, we find a vast gallery room containing all possible images.

From Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned, by Kenneth Stanley, Joel Lehman (2015):

Imagine this giant room in which every image conceivable is hovering in the air in one location or another, trillions upon trillions of images shimmering in the darkness, spanning wall to wall and floor to ceiling. This cavernous room is the space of all possible images. Now imagine walking through this space. The images within it would have a certain organization. Near one corner are all kinds of faces, and near another are starry nights (and somewhere among them Van Gogh’s masterpiece). But because most images are just television noise, most of the room is filled with endless variations of meaningless gibberish. The good stuff is relatively few and far between.

The nice thing about thinking of discovery in terms of this big room is that we can think of the process of creation as a process of searching through the space of the room. As you can imagine, the kind of image you are most likely to paint depends on what parts of the room you’ve already visited. If you‘ve never seen a watercolor, you would be unlikely to suddenly invent it yourself. In a sense, civilization has been exploring this room since the dawn of time. As we explore more and more of it, together we become more aware of what is possible to create. And the more you’ve explored the room yourself, the more you understand where you might be able to go next. In this way, artists are searching the great room of all possible images for something special or something beautiful when they create art. The more they explore the room, the more possibilities open up.

Possibility spaces. Kenneth Stanley and Joel Lehman are AI researchers, and this is how an AI researcher sees creativity. When you are an AI, creativity is a search problem. Your job is to find something that already exists out there in the space of possibility. It’s just waiting to be discovered.

There is something powerful about this notion of possibility spaces, both from a theory standpoint, and as a way of seeing. It causes you to approach challenges in a different way. You don’t need to be creative. The creative breakthrough already exists out there in the space of possibility. It’s just waiting to be discovered.

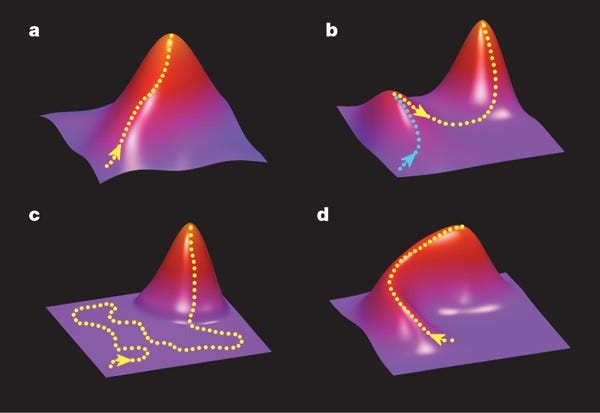

This way of seeing can be applied to many problem spaces. Evolutionary biologists can think of the possibility space of traits as a fitness landscape, or the possibility space of shapes and forms an organism can take as a morphospace. AI researchers can think of the loss function of an algorithm as making up a loss landscapes.

These landscapes of possibility can be smooth or rugged, static or dynamic (changing over time).

And a spatial metaphor suggests spatial actions. What dimensions make up the landscape of possibility? What does this space look like? Where are the most interesting things located? How can I effectively navigate through this space of possibility?

You start to see creativity differently. Maybe I don’t have to cover all of this ground myself? Maybe other explorers can map it out too? Maybe a computer can even help me explore it?

Related notes: Geists, Search reveals useful dimensions in latent idea space, Getting lost in the land of ideas.

The generative possibility space of DNA is unlimited:

Contemporary nucleic-acid-based replicators in living systems have, in contrast, unlimited heredity, and a museum showing all of the possible sequences up to a certain length would be larger than the Universe.

Szathmáry. The first two billion years. Nature 387, 662–663 (1997).

Note that Borges’ Library of Babel is not infinite. Each book is finite in length (410 pages), making the number of permutations finite. DNA has no such limit. The chain can always get longer. So, life is open ended, unlimited. Nature is endlessly finding new ways of being alive.

But not all replicators are unlimited. Interestingly, it seems likely that within the murky origins of life, the process becoming life was once limited, not open-ended:

G. Wächtershäuser (Munich) argues that the first replicators with limited heredity were much smaller molecules, with analogue rather than digital replication. Whereas analogue replication proceeds piecemeal, digital replication is a modular process.

Becoming unlimited was a major transition in evolution.

Note the powerful idea buried in this excerpt, mentioned in passing: there is a connection between modularity, composability, and open-endedness.

Related notes: Alphabets of emergence, Composability with other tools, Open-ended tools for infinite games.

Another book. The book of Minecraft worlds:

Imagine an enormous book, in which is a screenshot of every single Minecraft world. Each one is labelled with the world's random seed, a unique number you can type into Minecraft to get it to generate that world. The first page shows the world from seed 0, the next shows the world from seed 1, and so on. Minecraft's world generator contains 2^64 random seeds in total, which is a huge, huge number: that's 18,446,744,073,709,551,616 worlds that it can generate. Every time you click "New World", you get one of those seeds served up to you. This number, 2^64, is the size of Minecraft's generative space - the set of all the things it can generate.

Cook. Generative and Possibility Space. (2019)

Yet even this book does not contain all possible Minecraft worlds.

Now imagine a Minecraft world with nothing in it except flat grassland, forever, in all directions. No caves or rock underneath it, no trees, no hills, no animals. Just a single layer of grass tiles. Other than being pretty boring, this world isn't something you can generate in Minecraft (without modding it). We can imagine it, we can describe it, we can even open up Minecraft and create it ourselves by hand - but Minecraft can't generate it.

Cook. Generative and Possibility Space. (2019)

So there’s the set of things that are possible in Minecraft, and the set of things that are reachable via the generator engine.

Similarly, in nature there is the set of genes that are possible (unbounded), and the set of paths that our local evolutionary context is likely to explore. Evolution is path dependent.

The space of the possible and the space of the reachable.

Incidentally:

Here are some questions I’m asking myself as I think about possibility spaces and tools for thought.

What possibility spaces do my tools for thought generate?

Is the possibility space open-ended? In what ways might we expand the generative possibility space?

What parts of that possibility space are reachable, and how? What is path dependent? Where can I facilitate horizontal gene transfer between paths?

In what ways can I reframe creative challenges as a search problem?

The transition from analog heredity to digital DNA was a major transition that made life open-ended. What is analog that should be digital? What is integrated that could be modular? In my tool? In my notes? In what ways might those modules be composed, like DNA?

DNA is open-ended because the length of the chain is not bounded. Where am I limiting the length of my DNA chain?

Using a computer to generate permutations is a simple superpower for thinking. Where can I generate permutations?