Protocols as Weberian Bureaucracy

Have you noticed that people in small groups are pretty much self-organizing? We instinctually pitch in… and we keep tabs on who cheats, who shares, and who plays fair. Cooperation is literally built into our DNA, part of our evolutionary inheritance as a social species.

There’s a hitch, though. At about 150 people, our social instincts begin to break down. Coordination fails. Personal connections give way to power politics. This limit is called Dunbar’s Number. It seems to be a fundamental ceiling to our social cognition. Beyond 150, we need more than just instincts to cooperate.

So, let’s say you’ve grown past Dunbar scale. Now what? Max Weber says there are three ways power gets organized: rizz, rulers, and rules.

Rizz, or charismatic authority. Power is gathered by an individual through sheer force of personality. Heroes, martyrs, prophets, cult leaders, celebrities, founders, and dictators are charismatic authorities.

Rulers, or traditional authority: Power is enshrined and legitimated through ritual and custom. Elders, kings, priests, and politicians are traditional authorities.

Rules, or rational-legal authority: Power gets systematized. Rules are redesigned to produce particular results. Lawyers and law, bureaucracy and bureaucrats, modern states are rational-legal authorities.

Our political reality is messy, so every system ends up being an ad-hoc mix of these modes. Yet in many political systems, we can see a slow progression from rizz, to rulers, to rules. Why? Charismatic power is unstable, and meanwhile, we tend to enshrine the power structures we find around us:

There is something like a law of the conservation of institutions. Human beings are rule-following animals by nature; they are born to conform to the social norms they see around them, and they entrench those rules with often transcendent meaning and value.

(Francis Fukuyama, The Origins of Political Order)

Shielding charismatic power with tradition stabilizes charisma into something slower-burning, less prone to meltdown. Weber calls this process routinization. At its endpoint, we find the lowest-rizz institution of all: bureaucracy.

Bureaucracies are slow, they are impersonal, and they tend to ossify over time. For all these reasons, bureaucracy is mistakenly seen as a cost center to be removed, when it is actually a social technology for distributing power via rules.

The great advantage of distributing power via rules is that it scales. Personal power has limits to growth, because it is rooted in patronage networks, not in ability to get results. A system gets exactly what it select for, so:

Totalitarianism in power invariably replaces all first-rate talents, regardless of their sympathies, with those crackpots and fools whose lack of intelligence and creativity is still the best guarantee of their loyalty.

(Hannah Arendt, 1951. The Origins of Totalitarianism)

Being surrounded by sycophants is very enjoyable when you’re a tyrant without competition! On the other hand, it has serious downsides when you’re faced with a real threat. For this reason, early bureaucratic institutions often evolved out of war. Certainly in China this was the case, where the first modern bureaucracy developed during an intensely bloody period:

War was without question the single most important driver of state formation during China's Eastern Zhou Dynasty. Between the beginning of the Eastern Zhou in 770 B.C. and the consolidation of the Qin Dynasty in 221 B.C., China experienced an unremitting series of wars that increased in scale, costliness, and lost human lives. China's transition from a decentralized feudal state to a unified empire was accomplished entirely through conquest. And virtually every modern state institution established in this period can be linked directly or indirectly to the need to wage war…

Intensive warfare created incentives powerful enough to lead to the destruction of old institutions and the creation of new ones to take their place. These occurred with regard to military organization, taxation, bureaucracy, civilian technological innovation, and ideas…

It is safe to say that the Chinese invented modern bureaucracy, that is, a permanent administrative cadre selected on the basis of ability rather than kinship or patrimonial connection. Bureaucracy emerged unplanned from the chaos of Zhou China, in response to the urgent necessity of extracting taxes to pay for war.

(Francis Fukuyama, The Origins of Political Order)

Bureaucracy works! But it’s worth underscoring the ambivalence of rationalized power. “Rationalizing” is just organizing toward some instrumental goal, and that goal can be anything—liberatory, oppressive, beneficial, horrific. Even when it does good things, a bureaucracy does them like a machine: coldly, impersonally, routinely.

Rational calculation... reduces every worker to a cog in this bureaucratic machine and, seeing himself in this light, he will merely ask how to transform himself... to a bigger cog... The passion for bureaucratization at this meeting drives us to despair.

(Max Weber, Economy and Society)

Weber calls this increasing rationalization an iron cage. Caught in the logic of the machine, we feel bored and depersonalized. A bureaucracy may scale, but at the cost of draining the magic and adventure out of ordinary life.

Sometimes, we long for the days of heroes, when the villains were people, not systems. But unfortunately, when we break out of our iron cage, we don’t find freedom, just another charismatic dictator. Remove bureaucracy from a large system, and you don’t get efficiency, you get patrimonialism. Scale is hard, bureaucracy is cold, despots are mean. A dilemma.

So, yeah, bureaucracy isn’t always good, or fulfilling, or beneficial. But it has a redeeming quality: unlike despotism, bureaucracy can be designed, and that means it can be designed to approximate fairness.

I’ve been playing with seeing technology through Weber’s lens. After all, technology is made of people, and so it must go through this same routinization, from rizz, to rulers, to rules.

The ealiest stages of tech revolutions are driven by charismatic personalities—founders with heroic, prophetic, and dictatorial traits. Some get martyred.

As the technology passes the first inflection point, winning founders become kings. Power is still rooted in the founder, yet their individual personality begins to get eclypsed by the symbolic and ceremonial role of the ruler.

In the dusk of empire, the center of power becomes despotic. Its strategies shift to extraction. Everyone is unhappy. Open source projects spring up, attempting to unbundle the incumbent into public goods. Government moves in. The sector gets regulated, rationalized, and bureaucratized.

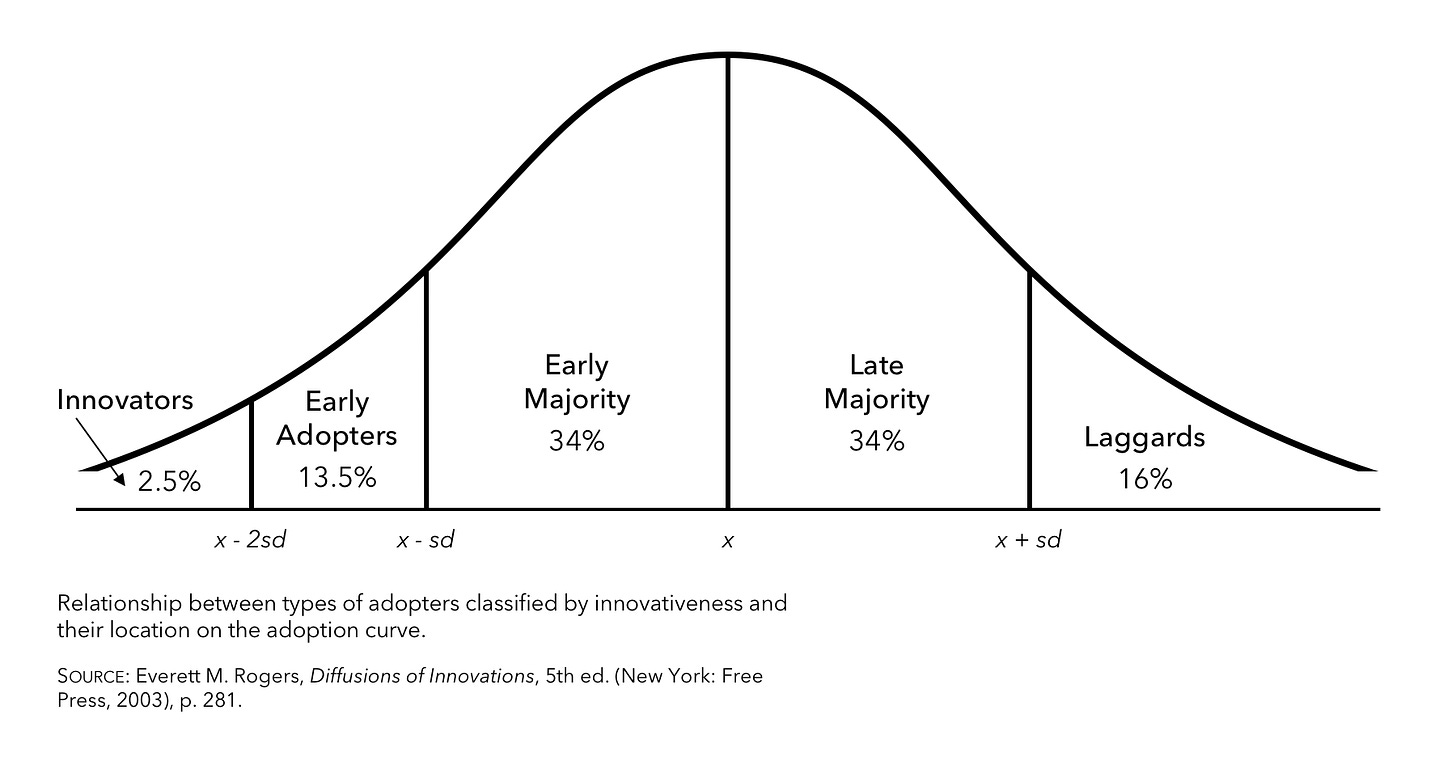

Mapped to the adoption curve, we get:

Rizz era: innovators and early adopters

Rulers era: early majority

Rules era: late majority and laggards

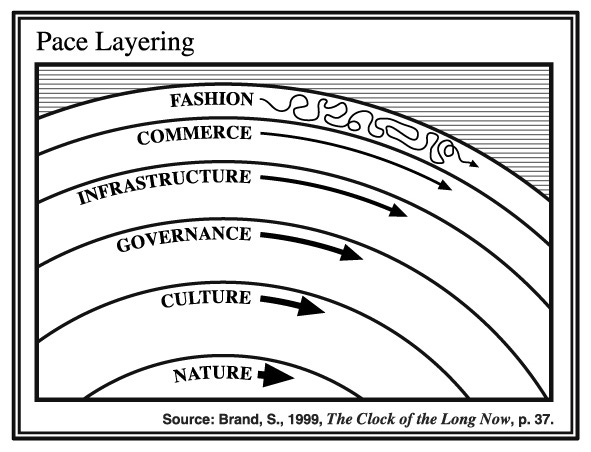

Or, through the lens of pace layering, we might say that rizz recedes with depth. From this perspective, we can see the slowness of bureaucracy as a feature. Products slowly transform into infrastructure, and this routinization creates a platform for new levels of rizz build on top.

Or, again, through Christensen’s Theory of Interdependence and Modularity, we might say that rizz creates industries, while rules modularize, commoditize, and scale those industries. In the idealized case, a technological value chain might go from product-centric, to platform-centric, to protocol-centric over the course of its evolution.

Of course, as in politics, the reality of our technological landscape is messy. Every system ends up being an ad-hoc mix of modes. Open source may fail to unbundle a late-stage category, or regulatory capture may further entrench a ruler’s incumbency through rules, or network effect may be leveraged to resist routinization.

The range of the possible is broad. Yet, we can imagine that each of these eras probably favors a different kind of elite personality—charismatic, traditional, managerial—and a different kind of technological approach. The s-curve shapes the playing field.

We can see both ends of Weber’s spectrum playing out in the 2024 technological landscape…

AI is a charismatic new technology, practically and symbolically represented by Sam Altman, a founder-hero-martyr, with a cult of personality.

Meanwhile, the social web is aging out of an era of rulers, and into an era of despots. This is most obviously exemplified by Twitter (“X”). Built by a charismatic prophet turned philosopher-king, it was foretold it should become a protocol. But instead, it was broken out of the iron cage by a charismatic billionaire with a dictatorial personality.

A wave of protocolization has been washing over the internet in reaction, starting in the summer of 2023, the summer of protocols. In the last year, Threads implemented ActivityPub, Bluesky grew to over 2 million users, Farcaster launched a permissionless network, and the IETF released a standard for end-to-end encrypted messaging. Heck, Noosphere is part of this wave too. The age of social media Caesars is waning. Even Mark Zuckerberg, the greatest of Caesers, has found new worlds to conquer. Jack has it right: the social web wants to be protocols.

So, Web 2.0 is dying; a protocolized internet struggles to be born. This protocolization represents last phase in a grand technological cycle. Meanwhile, at the leading edge, tech is exiting the era of managerial capitalism, and entering the era of charismatic personalities in the arena trying stuff.

Charismatic AI and bureaucratic protocols make up the explore / exploit arms of the next tech paradigm. AI eats the world, and protocolization scales it, by tackling the problems of data ownership, privacy, and attribution that currently act as limits to growth.