Specify it only somewhat

Fragments on agents, Dwarf Fortress, and tape loops

Reading this old essay by Brian Eno got me thinking about how we work with AI agents.

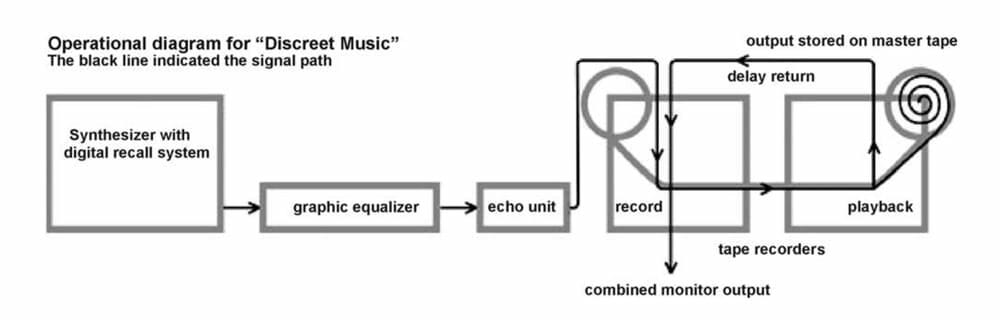

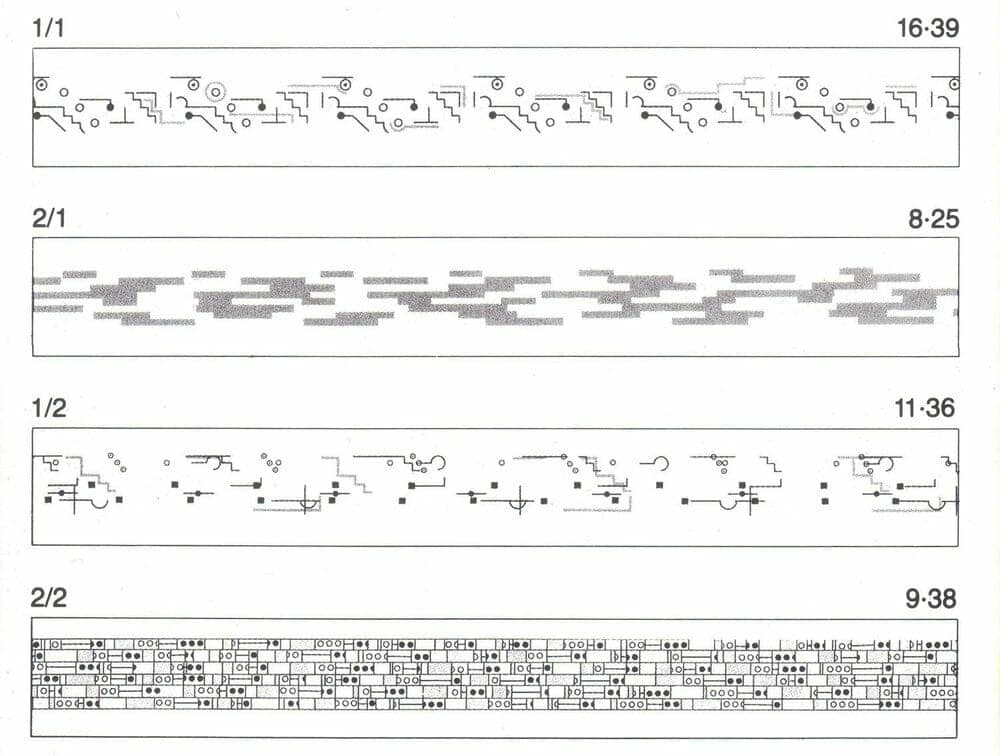

Eno was an early pioneer in the field of generative music. His Music for Airports is an example. It is composed of multiple tape loops—literal loops of tape, spliced together so they can be played around and around, indefinitely.

Eno stitched each loop together at a different length, winding tapes around the room, through chair and table legs, and back through the tape player. When played together, these tape loops gently phase in and out of relationship to each other, creating complex musical patterns that are rarely, if ever, repeated.

It’s a cybernetic approach to composition. Music as a system. As Eno puts it,

My contention is that a primary focus of experimental music has been toward its own organization, and toward its own capacity to produce and control variety, and to assimilate “natural variety” — the “interference value” of the environment. Experimental music, unlike classical (or avant-garde) music, does not typically offer instructions toward highly specific results, and hence does not normally specify wholly repeatable configurations of sound…. I hope to show that an experimental composition aims to set in motion a system or organism that will generate unique (that is, not necessarily repeatable) outputs, but that, at the same time, seeks to limit the range of these outputs.

(Brian Eno, 1976, Generating and organizing variety in the arts)

He later contrasts this bottom-up generative approach to the top-down approach of traditional musical scores. In a traditional score, you play the music. In a generative score, you play with the system that plays the music.

It seems to me that AI agents turn all of us into generative composers. Instead of writing the code, we write a generative score for agents to write the code. Instead of playing the music, we’re playing the system.

If you’re a programmer, this isn’t exactly new. We don’t actually write the ones and zeros the computer executes. We haven’t done that in a long time. Instead, we write the code that writes the code that writes the code that writes the ones and zeros.

So, in a sense, an AI coding agent just adds another layer to the cake. Agents generate code, which generates code, which generates code… However, the critical difference with agents is in the expressiveness of the generative system. Sure, a programming language like JavaScript allows us to express ourselves using higher-level concepts, and these are later compiled into ones and zeros. Yet JavaScript is still a formal language. It describes exact instructions, and the same script will generate the same exact instructions, every time. This is a bit like the traditional musical score, specifying how to play the music within fairly tight tolerances. A coding agent, by contrast, takes an English prompt, and extrapolates it into code. The agent is making an intuitive leap, from informal language, to a formal language, from a gesture, to a fully-specified set of instructions. There is a lot of ambiguity in that extrapolation process. The same prompt may generate different programs each time it is run.

But what if we see this ambiguity as a creative opportunity? Take Terry Riley’s In C, another generative piece. Its score is unusual:

All performers play from the same page of 53 melodic patterns played in sequence.

Any number of any kind of instruments can play. A group of about 35 is desired if possible but smaller or larger groups will work. If vocalist(s) join in they can use any vowel and consonant sounds they like.

Patterns are to be played consecutively with each performer having the freedom to determine how many times he or she will repeat each pattern before moving on to the next. There is no fixed rule as to the number of repetitions a pattern may have, however, since performances normally average between 45 minutes and an hour and a half, it can be assumed that one would repeat each pattern from somewhere between 45 seconds and a minute and a half or longer.

There’s a lot of ambiguity here. That ambiguity results in radically different performances. So here is a performance with Terry Riley,

…and another one, this time incorporating kora, balafon, and tama.

…and my personal favorite, by Invisible Polytechnic. It’s so energetic and cheerful.

The ambiguity of the instructions is what makes In C so special. There is no one exact way to play it. Individual performers are given the freedom to interpret the instructions for themselves, making every performance a surprise to the audience, and to the performers.

Instead of trying to specify it in full details, you specify it only somewhat. You then ride on the dynamics of the system in the direction you want to go.

(Stafford Beer, 1972, “Brain of the Firm”)

How might we adopt this creative stance toward AI agents?

There is no “correct” version of In C. The variety is the point… which is another way to look at this. In traditional programming, the coder has requisite variety to control the system, which is another way of saying that the system we’re working with, the system of code and compilers, is just not that complex. Its behavior can fit into our head.

Ashby’s Law of Requisite Variety: If a system is to be stable, the number of states of its control mechanism must be greater than or equal to the number of states in the system being controlled.

But working with an AI agent is different. Some of the complexity gets transferred out of our head, and into the head of the agent. The agent gains variety. Much more variety than a compiler. By working with it, we sacrifice some of our requisite variety, and lose some of our direct control over the system. But what if that’s good? Can we work with variety as a creative material?

How would Dwarf Fortress think about this? “You basically have a group of dwarves, and they mine in the mountains. You don’t control any specific dwarf, but you just kind of order their general activities…” Maybe the future of creative work looks more like Dwarf Fortress?

What if, as Eno suggests, our role as programmers, artists, designers, and thinkers, expands beyond playing the music, to playing with the system? To sculpting the variety of our agentic systems?