Strategy in four worlds

Different environments require different survival strategies

I’m building Deep Future, an AI that stress-tests strategies against thousands of possible futures via a realtime scenario generation engine. Think of it as Deep Research but for strategic foresight.

The research methods that ground Deep Future have roots in the Cold War, when RAND began adapting ideas from game theory and systems theory toward military strategy. By mapping the systemic forces driving change we can trace the outlines of futures that may emerge as forces collide. It’s a bit like forecasting, except instead of making specific predictions, we hold multiple scenarios in superposition, and use the contrasts like a wind tunnel.

Why map multiple futures instead of making particular predictions? The answer boils down to uncertainty. When uncertainty is within bounds, we can deploy the tools of risk management; things like portfolio theory, forecasts, and classical decision theory. However, extreme uncertainty fundamentally changes the strategic terrain. The heavy machinery of classical decision theory gets bogged down in the mud. Scenario planning, developed to help navigate the extreme uncertainty of conflict, can offer some traction.

Risk and uncertainty are two different things

The first thing to recognize is the distinction between uncertainty and risk. Risk is when you know the possible outcomes, and can assign probabilities to those outcomes. Uncertainty is when you don’t know the possible outcomes. These are two very different kinds of strategic situation.

Uncertainty must be taken in a sense radically distinct from the familiar notion of Risk, from which it has never been properly separated.... The essential fact is that ‘risk’ means in some cases a quantity susceptible of measurement, while at other times it is something distinctly not of this character; and there are far-reaching and crucial differences in the bearings of the phenomena depending on which of the two is really present and operating.... It will appear that a measurable uncertainty, or ‘risk’ proper, as we shall use the term, is so far different from an unmeasurable one that it is not in effect an uncertainty at all.

(Frank Knight, Risk, Uncertainty and Profit)

Rolling a six on a die is a risk. All of the possible outcomes are known and quantifiable. Aligning AGI is an uncertainty. The possible outcomes are unknown, and unquantifiable. We’re not sure what the space of possible intelligences looks like. We don’t know which paths through that space lead to alignment. We don’t even know if our concepts of alignment and intelligence are well-posed.

A pivotal question here is if we can identify the set of all outcomes. If we can, we’re dealing with risk. We can calculate expected utility and use classical decision theory. If we can’t, we’re dealing with Knightian uncertainty.

When we don’t know the possible outcomes, it is difficult to assign them meaningful probabilities. We have to grapple with uncertainty on its own terms. If we treat it like risk, it becomes too easy to assign false precision to unknowns, or just ignore the things we can’t quantify.

Uncertainty defines the strategic environment

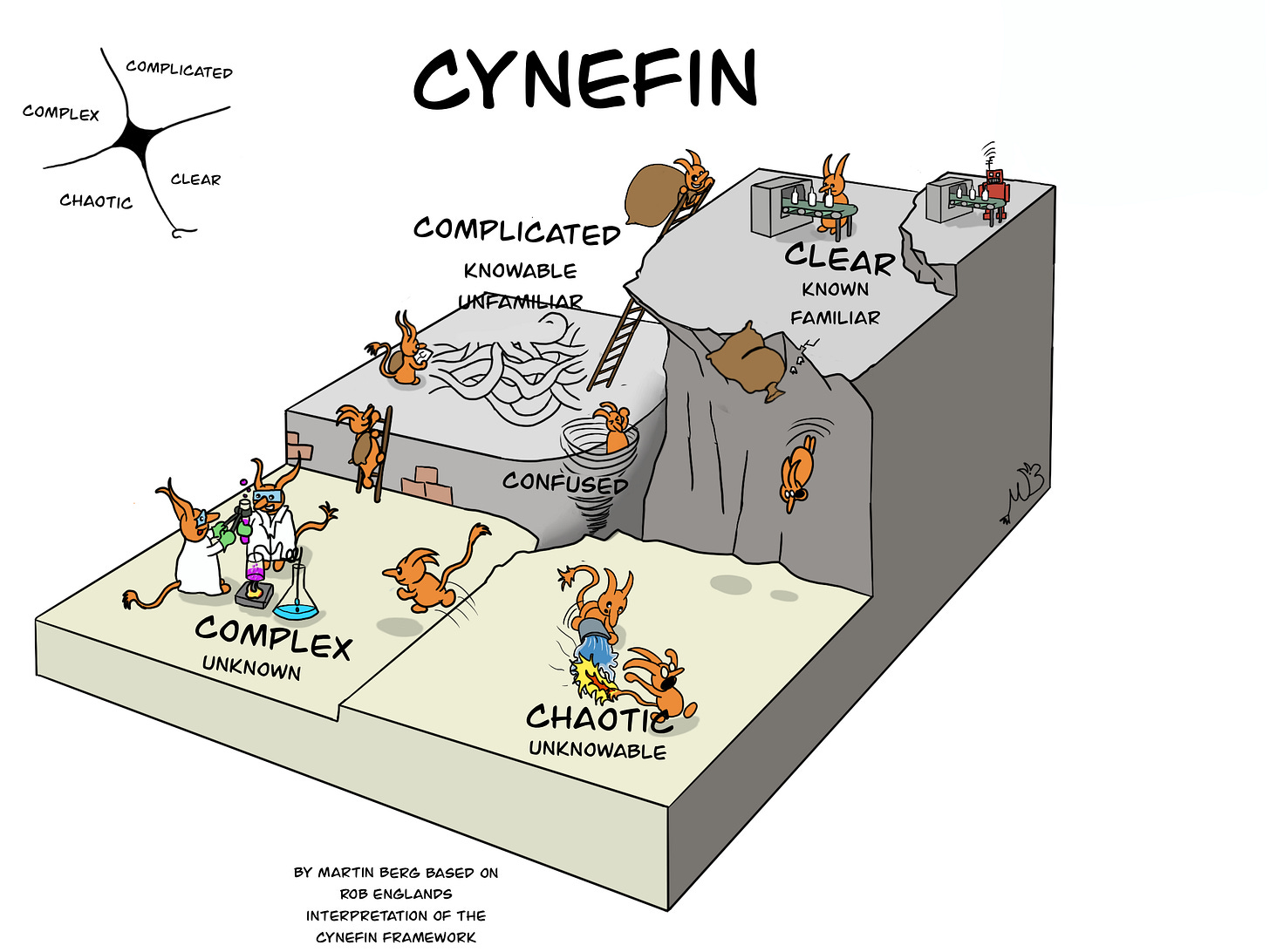

If we can’t quantify uncertainty, we can at least classify it. One useful heuristic is to divide uncertainty into four levels:

Clear environments are defined by known-knowns. The relationship between cause and effect is obvious.

Complicated environments hinge on known-unknowns. The important factors are knowable. There are direct relationships between cause and effect, but they might require expert knowledge and analysis to understand.

Complex environments are full of unknown-unknowns. The behavior of the environment is nonlinear. The relationship between cause and effect is indirect. The set of all possible outcomes is unknown, and often computationally irreducible.

Chaotic environments are structureless. The relationship between cause and effect is untraceable. Future states are unknowable and radically uncertain.

Production lines are clear, rocket science is complicated, climate change is complex, stampeding crowds are chaotic. If you don’t know which one you’re dealing with, you’re confused.

These quadrants correspond to distinct phase transitions we can observe in ecosystems. We could say clear, complicated, complex, and chaotic are archetypal patterns of behavior that emerge in ecosystems as they spiral upward in complexity. The increasing structure generates repeated patterns. More structure, more pattern, less uncertainty. Less structure, less pattern, more uncertainty.

Different environments require different strategies

Clear environments are dominated by risks. Complicated, complex, and chaotic environments are dominated by varying degrees of uncertainty.

A clear environment is basically a closed system. The rigid structure of clear environments generates very predictable patterns of behavior. The relationship between cause and effect is well-known. Decision theory is a no-brainer here. The important system states are all known and quantified, and we can easily calculate the expected utility of various strategies. At the extreme, we might even be able to apply automated optimization strategies.

Complicated space involves moderate amounts of uncertainty. The critical unknowns are mostly knowable in principle. However, putting bounds around these unknowns usually requires expert analysis.

An important quality of complicated and clear environments is that they tend to be ergodic, in the sense that we can poke the system without causing any fundamental changes to its structure or behavior. The relationships between cause and effect are linear. We can probe, measure results, and put bounds around key uncertainties. This allows us to apply optimization strategies, such as hill-climbing.

Superforecasting is highly effective in complicated environments. Detailed analysis of what is known allows a superforecaster to make highly educated guesses about what is not. The ergodic nature of complicated systems also means that we can often probe the system, identify possible outcomes, assign them probabilities, and practice Bayesian updating, without blowing anything up.

Things start to get muddier in complex and chaotic environments.

In chaos, all bets are off. Chaotic systems have no discernible structure, so prediction becomes almost useless. What we need are fast reflexes. Keep your eyes peeled, your ears open, and stay on your toes. This means expanding the Observe phase of the OODA loop, keeping Orientation simple, and Deciding and Acting as quickly as possible. The only success metric here is survival.

Complex environments are also dominated by uncertainty. However, unlike chaotic systems, there are patterns here. These patterns are driven by interacting feedback loops.

Because complex systems are driven by feedback, linear strategies that work in simple or complicated environments can generate unintended consequences in complex ones. To give a particularly stark example from The Great Leap Forward, when grain harvests didn’t meet expectations, sparrows were blamed for eating seeds and causing the shortfall. Therefore, the Party decided to eliminate the sparrows. Citizens were encouraged to kill sparrows by any means: shooting them down, throwing rocks, destroying nests. Hundreds of millions of sparrows were wiped out. A Soviet scientist present at the time recounts,

The results of this extermination drive were felt soon enough. The whole campaign had been initiated in the first place by some bigwig of the Party who had decided that the sparrows were devouring too large a part of the harvests… Soon enough, however, it was realized that although the sparrows did consume grain, they also destroyed many harmful insects which, left alive, inflicted far worse damage on the crops than did the birds. So the sparrows were rehabilitated. Rehabilitation, however, did not return them to life any more than it had the victims of Stalin’s bloody purges, and the insects continued to feast on China’s crops.

(Mikhail Antonovich Klochko, 1961. Translation by Andrew MacAndrew)

This man-made plague of locusts reduced harvests by 20%, leading to the deaths of two million people.

It is an extreme example, but characteristic of the disasters that happen when linear optimizers plow headlong into complex situations. Complex systems do not react to linear force in linear ways. This is because feedback loops make the relationship between cause and effect circular. The harder we try to optimize toward the goal, the more energy we pump into feedback loops. Eventually, some loop spins out of control, and the system kicks back.

“You see, when you get circular trains of causation, as you always do in the living world, the use of logic will make you walk into paradoxes. Just take the thermostat, a simple sense organ, yes? If it’s on, it’s off; if it’s off, it’s on. If yes, then no; if no, then yes.”

With that he stopped to let me puzzle about what he had said. His last sentence reminded me of the classical paradoxes of Aristotelian logic, which was, of course, intended. So I risked a jump.

“You mean, do thermostats lie?”

Bateson’s eyes lit up: “Yes-no-yes-no-yes-no. You see, the cybernetic equivalent of logic is oscillation.”

And it’s never just one loop. Imagine how multiple loops might feed into each other, damping or amplifying each other. You can see how the relationship between cause and effect becomes very complex indeed. Even small actions can produce big effects. The right move can generate exponential returns, or exponential collapse. The stakes are high.

There is no way to be a passive observer in such a complex system, since probing the network can alter its patterns of behavior in dramatic and irreversible ways. Complexity is non-ergodic, not a marble in a bowl that will roll back into equilibrium, but a dancing landscape, with multiple attractors, constantly changing, and being changed by our actions. It is difficult to assign probabilities to a fixed set of outcomes, when, in trying to discover the set of possible outcomes, we change the set of possible outcomes.

Scenario planning is for navigating complexity

To survive complexity, we need to accept some uncertainty. This means letting go of the optimal outcomes promised by expected utility. Instead of an optimal strategy, we want a robust strategy. We want to become antifragile to a wide range of possible plot twists.

This is where scenario methods come in. The first thing scenario planning helps us with is identifying major drivers and ballparking their level of uncertainty and potential for impact. During scenario research, we systematically catalog the forces driving change, tracking trends across social, technological, environmental, economic, political, and other categories. Maybe we can’t pin exact numbers to everything, but we can spot many of the unknowns and put bounds around them. Systematically cataloging and grading forces like this often surfaces important strategic factors that would otherwise be missed. We especially want to keep an eye on weak signals that could have high potential impact. Using superforecasting techniques can be very high-leverage here, and in fact, the kind of cataloging and grading we do in this phase looks a lot like the detailed estimation that a superforecaster does before making a forecast.

Another thing that scenario planning helps with is mapping connections between forces and between actors in the environment. This surfaces many of the feedback loops that can generate nonlinear behavior in a complex environment. Spotting these feedback loops can give us a good sense of what might spin out of control, or, taking another perspective, where the systemic leverage points are.

Using this map of our strategic environment, we can also generate numerous research-grounded scenarios. These scenarios emerge from the intersection of trends that we can point to in our environment today. Rather than attempting to predict one or the other future, we use these scenarios—particularly the divergent scenarios—to wind-tunnel strategies. This helps us develop strategies that are robust across many possible futures. We can even develop multiple contingency plans to deploy in one scenario or another.

Most interesting to me, scenario planning can help us shape the future by articulating a range of possible futures we can aim for. Used in this way, a scenario is prescriptive rather than descriptive. Instead of debating the odds of a scenario like a spectator, we can use scenario planning to tilt the odds in our favor. The best way to predict the future is to create it, after all. In this view, scenario planning is more like map of leverage points that we can push on, to try to bring about particular futures.

Reality is bigger than any one model

These are all just heuristics. Reality is never just one thing. Real strategic challenges involve a wide range of problems and sub-problems, some clear, others complicated, complex, chaotic, or in-between.

I was chatting with Nuño Sempere about all of this recently. Nuño is an advisor to Deep Future and a superforecaster who’s team won the CSET-Foretell forecasting competition by a surprising margin—“around twice as good as the next-best team in terms of the relative Brier score”. So Nuño is someone you want to listen to when it comes to the future. Anyway, he described the experience of trading between foresight and forecasting techniques as almost a yin-yang kind of thing. The skilled strategist freely borrows from a wide repertoire of strategic tools, including forecasting, scenario planning, decision theory and everything else. This instinct is a kind of tacit knowledge learned in the trenches. Can we infuse some of it into an AI agent? I’m optimistic.

We’re developing Deep Future alongside a limited number of exclusive founding partners. Interested? Reply to this email, or join the waitlist.